ExPRS

Background

Complex traits are influenced by genetic risk factors, lifestyle, and environmental variables, so-called exposures. Some exposures, e.g., smoking or lipid levels, have common genetic modifiers identified in genome-wide association studies. These exposures an impact disease risks. For example, high body mass index, smoking, blood lipid levels, and pre-existing type 2 diabetes (T2D) were recognized as prominent risk factors for cardiovascular disease,8 respiratory diseases,9 and cancers.10,11 Given the relevance for these often modifiable risk factors for morbidity and mortality, exposure information is pivotal for precision prevention.10 However, data on even common exposures are not always available, especially when using electronic health records (EHRs). Furthermore, data can be prone to measurement error, bias, and non-random missingness.12,13 Yet, some exposures have a heritable component identifiable through GWASs14,15 and thus offer the opportunity to construct exposure PRSs (ExPRSs).

Overview of our study

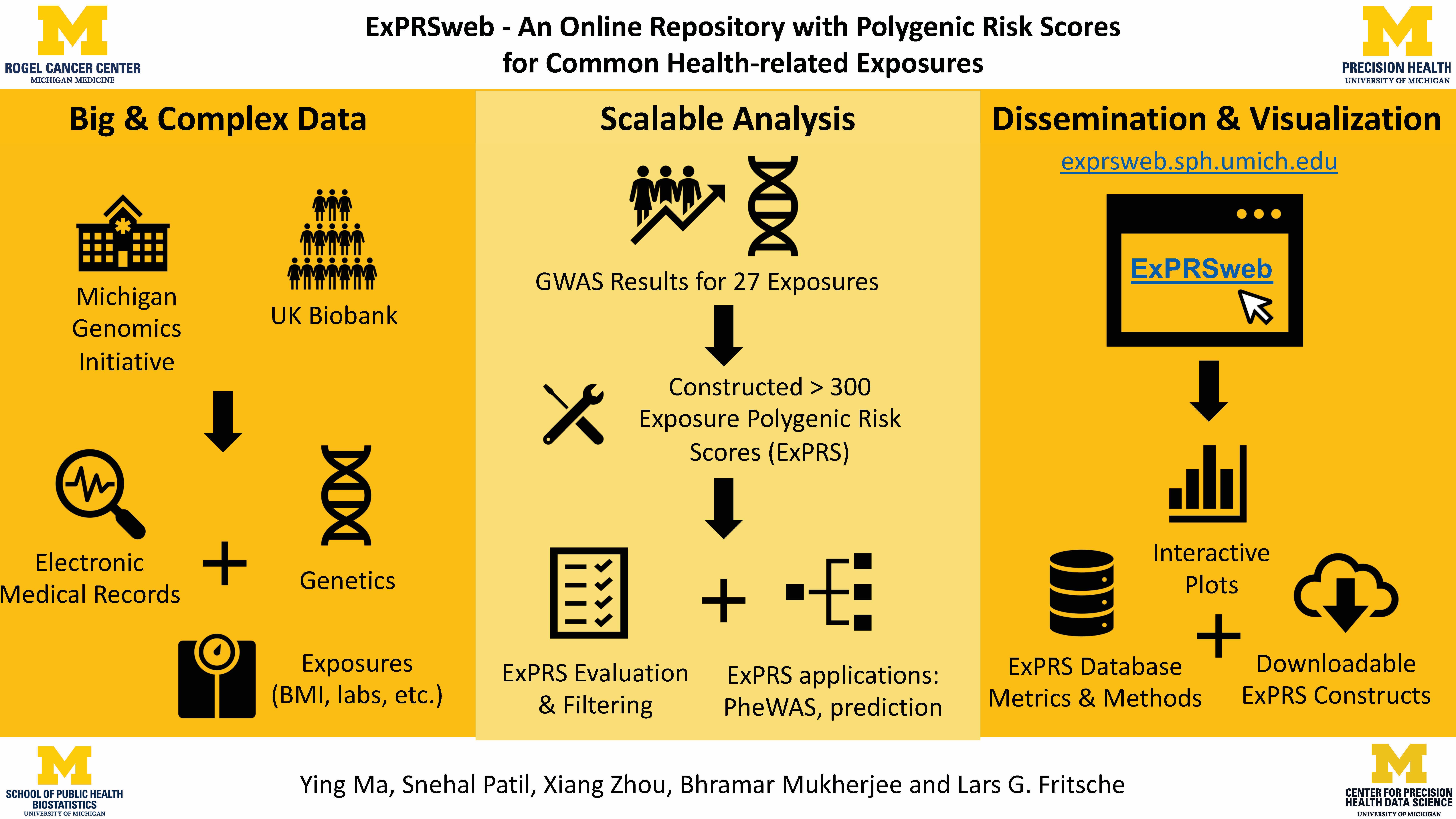

By using available exposure GWAS summary statistics and two large biobanks, the Michigan Genomics Initiative (MGI) and the UK Biobank (UKB), we generated ExPRSs with four methods varying in complexity and modeling (i.e., linkage disequilibrium clumping and p value thresholding [C + T], Lassosum, deterministic Bayesian sparse linear mixed model [DBSLMM], and PRS-CS, a Bayesian method with continuous shrinkage priors).We also highlight ExPRS applications including PheWAS, risk stratification, and prediction of common chronic conditions. For the latter, we evaluated the predictive performance of single and multiple ExPRSs when combined with disease-specific PRSs and could show substantial improvement for several traits. We also contrasted these predictors with “poly-exposure risk scores” (PXSs), which integrate multiple measured exposures. In absence of high-quality exposure data on many individuals, ExPRSs can serve as surrogates if one has genotype data on a larger and more representative sample. Our repository ExPRSweb unlocks access to over 300 ExPRSs for 27 different exposures and facilitates scientific collaboration to strengthen their future application.

Paper

ExPRSweb: An online repository with polygenic risk scores for common health-related exposures

Paper Published in The American Journal of Human Genetics

For previous papers related to the polygenic risk score research, please find more details in the following list:

Paper Published in Trends in Genetics

Paper Published in The American Journal of Human Genetics

Paper Published in Plos Genetics

Selected important results

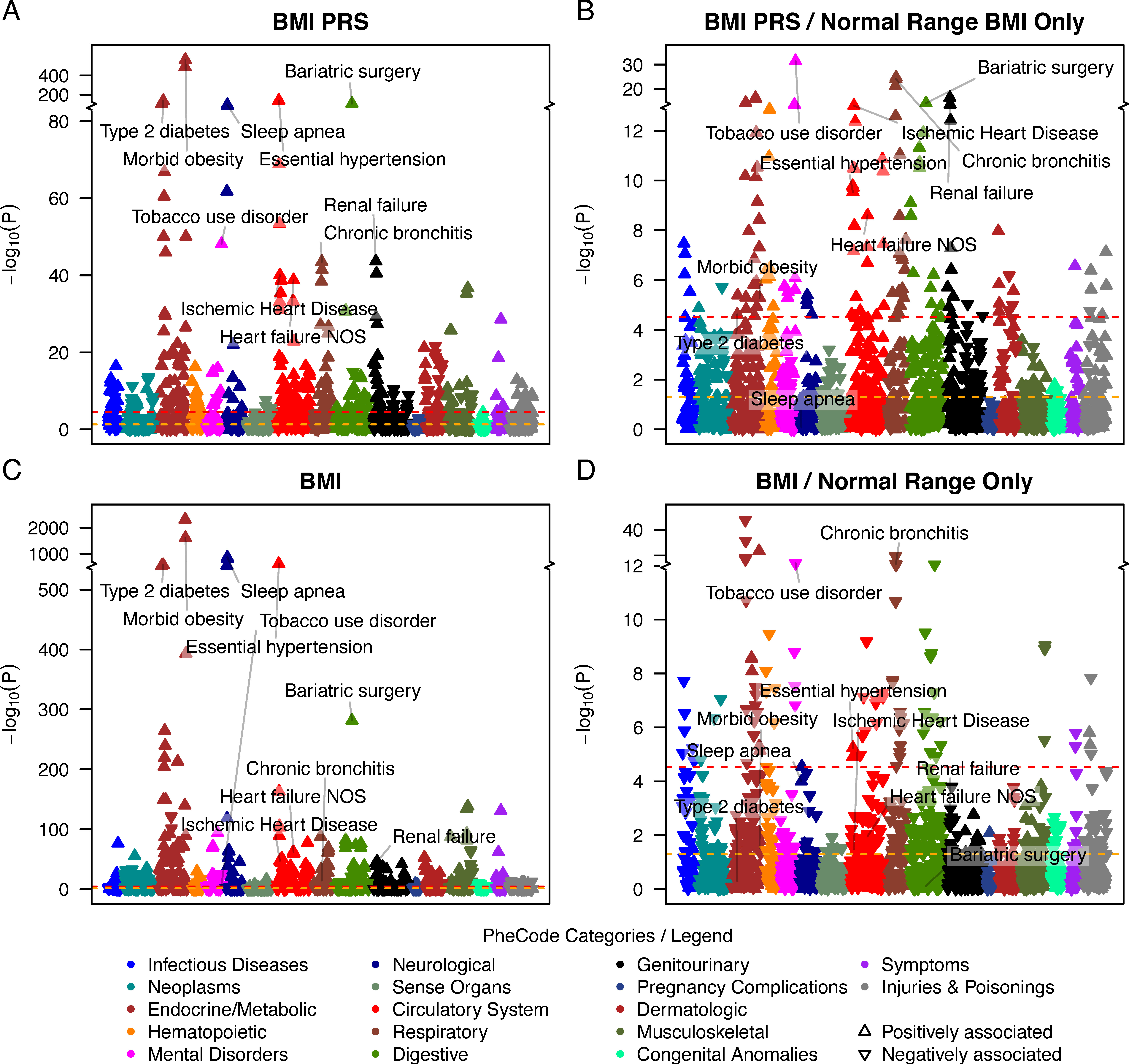

One application of ExPRSs is their use as predictors for phe- nome-wide association studies (PheWASs) to uncover phe- notypes with a shared genetic component and thus disorders that might benefit from an early intervention. We showcase such ExPRS PheWASs by analyzing all 24 selected ExPRSs across up to 1,685 EHR-derived phenotypes (PheCodes) in MGI. Here are the results showing PheWAS with the BMI ExPRS uncovered 329 associated phenotypes. To assess whether these associations were driven by exposed individuals, i.e., individuals affected by a binary exposure or by low or high exposure values, we also performed ‘‘exclusion-PRS-PheWAS’’ analyses where we excluded such exposed individuals to remove direct and in- direct associations of the exposure and potential treatment effects. For example, in the exclusion PheWAS with the BMI ExPRS, the associations with hypertension (OR: 1.17 [1.12, 1.23]) and T2D (OR: 1.18 [1.09, 1.27]) remained statistically significant. However, while the analysis of individuals with healthy BMI removed most of the obesity or overweight phenotypes, a strong association remained between BMI ExPRS and bariatric surgery (OR: 2.66 [2.08, 3.41]). A closer inspec- tion revealed that 73 of 1,509 MGI participants who under- went bariatric surgery had recorded median BMI values that fell in the healthy BMI range (18.5 < BMI < 25), indicating the BMI ExPRS’s ability to capture pre-treatment exposures. Most interestingly, the corresponding exclusion PheWAS with measured BMI as predictor revealed many association signals that were reversed compared to the exclusion-PRS- PheWAS. This finding might reflect biased measurements, e.g., due to treatment or interventions that result in normal BMI values, or the measured BMI’s inability to capture central obesity.